Sampled + Sorted moves to Tumblr

Last month, I swapped my personal blogging over to Tumblr. I may still post the occasional “essay” over here, but the short multimedia posting action on Tumblr seems the right fit for now. Check it out here.

Filed under: Uncategorized | 1 Comment

We just launched 2 great new pages aimed at giving both listeners and DJs an easy way to review “new stuff” of interest on 8tracks. (Re-posting from company blog at http://8tracks.tumblr.com/ as not sure how to do automatically yet.)

For listeners:

We now offer a Tumblr-like “mix feed” that serves up, on 1 page, all new mixes by people you follow on 8tracks. (Click the big “+ Follow” button next to a DJ’s pic to follow him/her.) This mix feed is, in effect, your personal “station” — programmed by people whose taste you trust — and now lives on your homepage (if you’re logged in and are following at least 1 person).

For DJs:

We now offer a dedicated Comments page that aggregates all of the comments a DJ receives on his/her mixes. Previously, a DJ had to click into each of his mixpages to see if anyone had left comments. This often meant that DJs didn’t notice new comments on a timely basis. Now, you won’t miss a comment. (We’ll provide an in-line Reply option from this page soon.)

Check ‘em out and let us know what you think.

Filed under: ventures | 1 Comment

There’s a subtle but important distinction between what 8tracks offers as compared with what Last.fm or Pandora provide.

I enjoy both Last.fm and Pandora and have written about them in the past. Both deliver a radio-style experience that is personalized based on one’s preferences, as captured explicitly (I enter the name of an artist) or tacitly (AudioScrobbler tracks what I listen to on iTunes). Last.fm applies collaborative filtering to create a personalized playlist, while Pandora uses the results of the Music Genome project to do so. This is a great way to discover new music.

8tracks also provides a passive, radio-style experience. But the programming is done by people who love and know music, not algorithms. In many cases, the resulting playlist contains music that is “similar” but extends beyond the sound itself to contemplate social context, era, a theme or other factors. In addition, the human element lends the opportunity for eclecticism and serendipity that may be absent from an purely algorithmic approach.

As I mention in our About section, our basis for taking this approach is rooted in compelling shared programming of times past: think radio in the 1970s, mixtapes in the 1980s, and DJ culture in the 1990s through today. Everyone knows a few people who know great music — the friends that introduce you to new (or old) music, that make compilation CDs, or that are “real” DJs and play out somewhere. Our goal is to give these people an simple way to reach a larger audience.

Which leads to another critical point: 8tracks is not about “personal listening” in the sense of a user goes to 8tracks.com and makes a playlist and then turns around and listens to it himself or herself. That is not the objective of the service. Rather, we seek to provide a useful, legitimate platform so that those relatively rare people with the knowledge and time to make great playlists can do so for others who love music and want to discover new artists, but who simply don’t have the time to do so themselves.

That’s what we’re about: to help the majority of our users save time and kick back, while giving the music mavens (to use a Gladwell-ism) a simple solution to exercise their craft online.

Filed under: >> music, discovery, ventures | 2 Comments

8tracks

As many of you know, I’ve been focused on a new digital music venture for about 2 years now, starting with a pretty “web 1.0” path (write business plan, create financial model, talk to VCs) and subsequently wising up to a more pragmatic approach (tap friends and 401k, build and iterate on product, attract people to site).

I’ve been working with a talented group of friends over the last year to get this new service, called 8tracks, off the ground. We launched an alpha version of the site at the beginning of the year. Informed by feedback, our team — including our first full-time developer, Rich Caetano — launched a beta version of 8tracks about a month ago. We’ll be bringing in new users over the next 2 weeks, before public release a week from Friday, on August 8th.

The new 8tracks blog is up and running, and our first substantive entry explains more about 8tracks.

Please check it out and let us know what you think!

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a Comment

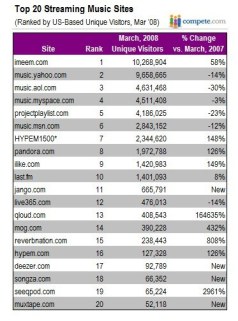

Top 20 music sites – March 2008

Compete.com launched its own ranking of top music sites, probably saving me a lot of work going forward. Helpfully, the new rankings also include the music subdomains on Yahoo, AOL, MySpace, and MSN. They’re still missing a few of the smaller sites, but I reckon they’ll add the others in due course.

Upshot is that imeem now tops Yahoo, and Eliot Van Buskirk has a nice rundown on some of the reasons for the shift away from Yahoo. Here’s the ranking:

Filed under: discovery, valuation, ventures | 9 Comments

While I’m on this list-making tip, I just noticed SAI is now tracking the most valuable digital startups. This is a useful list and includes details on how the valuations were estimated. I like the fact that the list is global and features some surprises, at least for me:

- FB and Wikipedia top the list at $9bn and $7bn, respectively

- London-based Betfair is worth as much as Craigslist ($5bn)

- Habbo and Linden Labs both worth > $1bn

- Ning already worth >$500m (that seemed quick)

- Zazzle at $250m (also seemed quick)

- Surprisingly, Meebo is worth nearly as much as Yelp (both ~$220m)

- USV investments make the list: Etsy ($115m) tops Twitter ($75m)

- Wesabe doesn’t make the cut though rival Mint does ($50m)

Fascinating stuff.

Filed under: Uncategorized, valuation, ventures | Leave a Comment

Based on the definition of total attention in my last post, I thought it’d be interesting to rank the top 10 music sites. To do so, I multiplied “visits” by “pages/visit” (both per compete.com). Assuming these numbers are accurate, the product is the total page views served up in a month and should give a sense of both the total amount of consumer attention commanded by a site and the visual ad “avails” on that site.

Here’s the rankings that result, and to provide a sense of relative magnitude, I’ve pegged Live365’s pages at 1.00:

- imeem (550m pages / 12x size of Live365)

- Project Playlist (378m / 8x)

- Live365 (47m / 1.00)

- Pandora (46m / 0.98 )

- Napster (30m / 0.65)

- Rhapsody (23m / 0.50)

- Last.fm (18m / 0.39)

- iLike (17m / 0.37)

- Jango (11m / 0.23)

- Qloud (6m / 0.13)

I’m still a bit surprised by this, as I’d have imagined the social networking plays in this group (Last.fm, iLike, Jango) would generate relatively more page views than the radio-focused plays (Live365, Pandora).

Note that the on-demand and primarily subscription-based services (Napster and Rhapsody, which now have an ad-based, or at least free, web offering) fall smack in the middle on this measure. As with a ranking by unique visitors, imeem and Project Playlist still come out on top, by a wide margin.

I’d love to hear others’ thoughts on these rankings, and I’m happy to send anyone who’s interested the spreadsheet I used to calculate these rankings.

Filed under: discovery, valuation, ventures | 7 Comments

I wrote on Wed about the notion of “total attention” as a useful metric by which to evaluate music or other websites — but didn’t explain my thinking or actually run the numbers.

As so many have written over the last decade, a large and growing proportion of GDP comprises products and services that are (or can be) rendered in bits. As it becomes ever cheaper to create, copy and distribute bits, scarce resources in production (broadly defined) are increasingly giving way to scarce resources in consumption – i.e. consumer attention. As an aside, this is why I’ve long believed (and Chris Anderson eloquently wrote a few years back) that the most significant driver of value for digital products is really just “matchmaking” or filtering or discovery. That is, helping people find those bits of greatest interest from the digital haystack, so to speak.

In any event, if consumer attention is the most precious resource in the digital value chain, then its proper measurement is critical. Further, I’d argue that the more attention a web offering can command, the greater the opportunity for monetization, all else equal. If a person visits more pages on a website, listens to more minutes of a webcast, or uses another web-based service more frequently, there are more opportunities to place promotional or branding messages, whether priced on a CPM, CPC, CPA or other basis.

Likewise, a user’s choice to spend more of his “disposable” hours in the day on a website/cast/service also suggests that he ascribes greater value to it, and — again, all else equal — there is a greater likelihood he may be willing to pay directly for some aspect of that product, whether priced on an a la carte (commerce) or ongoing (subscription) basis.

To measure the total attention that a web offering commands, 3 factors must be considered:

- unique visitors

- frequency of visits (e.g. avg visits/unique)

- average “stay” per visit

While average stay per visit (e.g. minutes on site) would seem a logical measure to assess the magnitude of a visitor’s activity on site — since it tracks the total minutes of attention granted — another, perhaps more practical measure is page views per visit. Page views per visit is useful b/c it (1) generally corresponds to new ad placement opportunities (with each page refresh), and (2) ensures that a user is “active” on the site and does not simply have the browser open in the background while, say, writing an email.

So then total attention can be defined in 2 ways:

- unique visitors x visits/unique x minutes/visit = total minutes of attention

- unique visitors x visits/unique x pages/visit = total pages of attention

I used compete.com to rank the top 10 music sites on the latter basis (the former really won’t make sense until online audio ads move beyond a nascent stage). As this post has gotten a bit overlong, I’ll include these rankings in a new post.

Filed under: discovery, Uncategorized, valuation, ventures | 2 Comments

Stickier music sites

If one assumes advertising (or other sorts of attention-based business models) will be the primary driver of revenues for online music services — or really any online services — then a total measure of attention is useful in establishing the value of the service.

I’ve generally presented music sites ranked by “people” (compete.com’s version of unique visitors). But really a total measure of attention should reflect:

- unique visitors

- frequency of visits (e.g. avg visits/mo)

- average “stay” per visit

I checked a few of the top music sites on the average stay measure and found some intriguing results:

I’m guessing that some of the reason Live365 ranks so highly has more to do with its user base (older, more passive) than specific site features. But it is somewhat surprising.

Filed under: Uncategorized, valuation, ventures | 3 Comments

Top 25 music sites – March 2008

I haven’t updated the music 2.0 rankings for quite a while. There’s some very cool (albeit legally questionable) new players on the horizon (Muxtape and Mixwit), and several existing sites have demonstrated serious growth (like Qloud, just acquired by Buzznet, and Jango, which seems to have come out of nowhere).

This time round, I’ve dropped the two-point-oh designation and picked up old-schoolers Rhapsody and Napster, increasingly useful now that many services are offering legal on-demand access (e.g. Last.fm now does on-demand in addition to radio, imeem now is licensed to offer on-demand access). I wanted to include the music offerings from Yahoo, AOL and MSN but can’t seem to get subdomain data.

I’m probably still missing some sites that ought to be on here. I know that MySpace and Buzznet (and, to a lesser extent, the other big social networks, most of which have some sort of music component) could arguably be included too. I’ve kept imeem because music is such a big component to their service; MySpace is the tacit #1 service.

Lastly, I’m not sure what’s up with the retroactive change to imeem’s numbers but it’s now showing a huge increase in prior months over what had previously been reported.

Filed under: discovery, valuation, ventures | 3 Comments

Tags: >> music, ilike, imeem, last.fm, music 2.0, pandora, project playlist

You must be logged in to post a comment.